How much have countries increased defence spending?

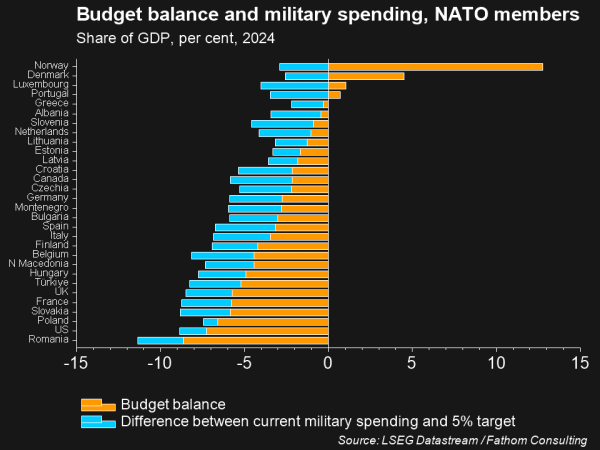

Following US President Donald Trump’s repeated calls for allies to start pulling their weight in defence spending, the member countries in the North Atlantic Treaty Organisation (NATO)—excluding Spain—have pledged to meet Trump’s demands of defence spending at 5% of GDP. Mark Rutte, Secretary General of NATO, revealed the commitment involves a 3.5% increase on core military expenditure and 1.5% increase on infrastructure and cybersecurity by 2035, well above the previous 2% total spending target. Rutte also praised Trump for pushing NATO to its latest commitments, saying how “dear Donald” has driven them to “a really, really important moment for America and Europe1.”

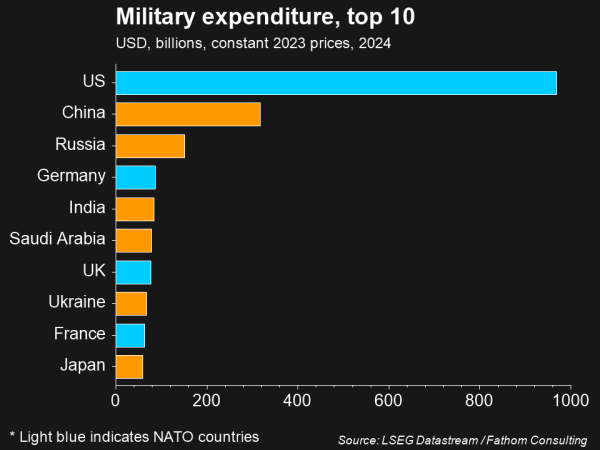

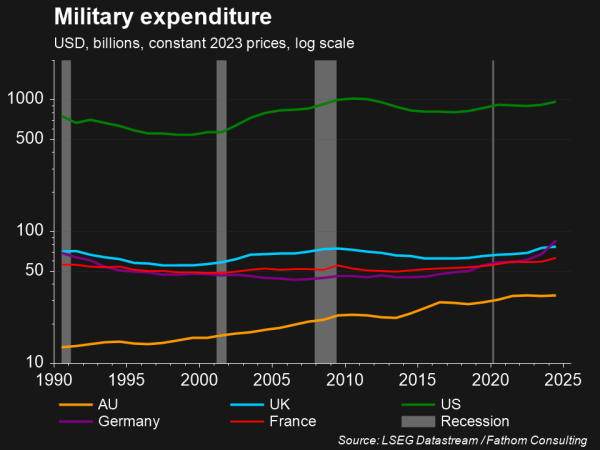

Germany has emerged as the spending leader in Europe following the NATO decision, pledging a 70% increase in military expenditure to €162bn by 2029, including about €8.5bn in aid per year to Ukraine until 2029. This would bring core defence spending to about 3.5% of GDP over the next four years from about 2.4% in 20252.

In Asia-Pacific, responses to Trump’s calls have been more muted. With Japan scrapping its July 1 meeting with the US, after they asked Japan to boost defence spending to 3.5% from around 2% currently. Australia, with defence spending also at 2% of GDP, has similarly been set this 3.5% target by Trump. Prime Minister Anthony Albanese has responded by saying, “we’ll determine our defence policy.” This follows the Pentagon launching a review of the 2021 AUKUS nuclear submarine pact, throwing the deal into doubt3.

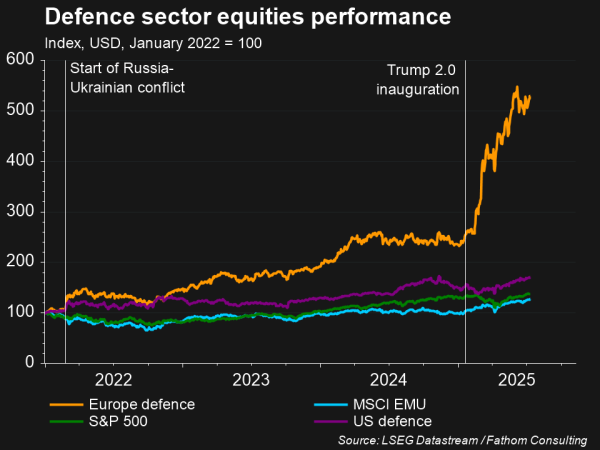

How have defence stocks performed?

These updated spending commitments from NATO and other US allies, have seen defence stocks rocket. Furthermore, compounded by the ongoing war in Ukraine, tensions in the Middle East, and China-Taiwan risks that have heightened geopolitical uncertainty. This has then significantly increased investors’ expectations for spending on both traditional defence systems, like fighter jets from SAAB (SAAB-B.ST), and new technologies like cybersecurity and AI-enabled data processing from Palantir (PLTR:NASDAQ).

As opposed to the last few decades, investors are therefore pricing in a decrease in the ‘peace dividend’—a term used to describe the economic benefits of a decrease in defence spending’—as countries instead ramp up military expenditure in response to geopolitical tensions and decreasing globalisation. Defence spending is also highly agnostic to broader economic conditions, due to expenditure commitments typically being mandated in government budgets. Which has appealed to some investors over the last year who have sought protection from the economic uncertainty brought on by Trump’s tariffs.

What about bond markets?

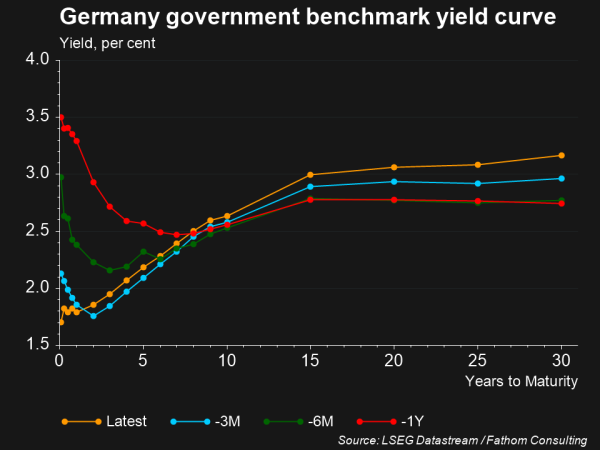

Increases to defence spending commitments have seen investors’ expectations for future budget deficits to ramp up, especially for European nations aiming to meet Trump and NATO’s new 5% target by 2035. Germany, most notably, has relaxed its constitutional debt cap to allow up to €1 trillion in borrowing for defence and infrastructure spending in the next decade. The budget deficit is forecast to more than double to €82 billion this year from €33 billion last year, before reaching €126 billion by 2029. This expectation of greater bond issuance to fund deficits in the years ahead has seen long-dated bond prices fall, as investors expect more long-term supply—subsequently increasing long-dated yields and causing yield curves to steepen.

It remains to be seen whether countries will meet their defence spending targets, but regardless we are no doubt in a period of heightened geopolitical uncertainty, that defence companies may continue to benefit from going forward.

Further reading

See our approach to ethical and sector exclusions in Responsible Investing.

References

- Financial Times, “Nato chief Mark Rutte praises Donald Trump for making Europe ‘pay in a BIG way,’” 24 June 2025

- Financial Times, “Germany to boost defence spending at faster rate than France or UK,” 24 June 2025

- Financial Times, “Pentagon launches review of AUKUS nuclear submarine deal,” 12 June 2025