What has sparked the latest concerns about private credit?

Private credit has rapidly evolved into one of the fastest-growing segments of global finance, expanding from roughly $US2 trillion in 2020 to more than $US3 trillion today1. The private credit market appeals to investors by offering higher yields than traditional bonds while financing companies underserved by banks. In the United States, the market is structured around Business Development Companies (BDCs), which combine private credit exposure with public market oversight. These listed vehicles trade on major exchanges and are required to disclose quarterly valuations, credit metrics, and fair-value methodologies, bringing a degree of transparency to the asset class.

Yet recent events have exposed vulnerabilities that have unsettled investors. Earlier this year, Blue Owl Capital, a major US private credit manager with approximately $300 billion in assets under management, proposed merging two of its BDCs, one publicly listed and one private2. Investors in the private fund, Blue Owl Capital Corporation II, were to receive shares in the listed BDC, OBDC, at net asset value (NAV). OBDC, however, was trading at a 20% discount to NAV, meaning investors would have taken an immediate paper loss of roughly one-fifth of their holdings.

This episode underscored the inherent valuation opacity in private credit. Unlike public bonds, these loans are not marked to market but are “marked to model” using internal fund manager models and assumptions, which can mask stress in underlying borrowers. In Blue Owl’s case, the sharp discount between its listed BDC’s market price and reported NAV signalled that public investors perceived greater credit risk than the valuations reflected, highlighting the gap between modelled values and market sentiment. Blue Owl ultimately abandoned the merger, citing “market conditions,” but not before its own shares fell almost 40% year-to-date3. Redemptions in the $US1 billion Blue Owl Capital Corporation II surged to $US150 million in the first nine months of 2025, up 20% from last year, with $US60 million withdrawn in Q3 alone. These figures underscore a growing tension, as investors, drawn to private credit for its high yields, are discovering the liquidity constraints and valuation risks inherent in the asset class.

What about the broader private credit market?

The Blue Owl saga coincides with a series of unsettling developments in US credit markets. The collapse of First Brands, an auto-parts maker with $10 billion in liabilities, and Tricolor, a subprime auto lender, revealed cracks in consumer finance and private lending4. Both companies went under without lenders marking down their loans beforehand, raising questions about whether private credit managers are slow to recognise distress. In fact, some BDCs were still valuing First Brands’ debt at $US0.90–$US1.01 on the dollar just months before bankruptcy5.

Following the bankruptcy, JPMorgan CEO Jamie Dimon stated that “when you see one cockroach, there are probably more,” reflecting fears that these credit blow-ups may not be isolated but symptomatic of wider issues.

Where are the cracks emerging?

Liquidity mismatch is one of the most pressing concerns. Private credit funds promise periodic redemptions, but their assets are illiquid, meaning when sentiment turns, managers may impose “gates” to prevent fire sales. Valuation gaps are another issue. Unlike public markets, private credit depends on internal models, which can obscure real-time risk. The First Brands case showed loans marked near par value just before bankruptcy, undermining confidence in reported figures.

Concentration risk is also evident. In Australia, ASIC’s review found that half of private credit exposure is tied to real estate, amplifying vulnerability in a property downturn. Interconnectedness adds another layer of complexity: US insurers now hold $US685 billion in illiquid private assets6, and banks have lent $US525 billion to private credit funds7. These links could transmit stress across the financial system if defaults rise.

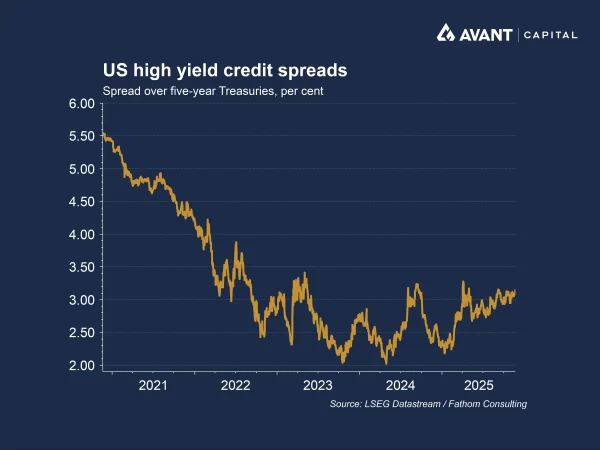

While these issues do not yet point to systemic contagion, high-yield credit spreads, though still tight by historical standards, have widened notably since the beginning of the year as investors respond to recent private credit defaults such as Tricolor. This trend raises questions about how the broader private credit sector may perform should economic conditions deteriorate.

Private credit continues to play a crucial role in filling the gap left by banks after the global financial crisis. However, investing in the sector demands vigilance, and investors must weigh whether the promise of higher yields for elevated risk meets their financial goals and risk tolerance.

References

- Reuters, “Blue Owl fund redemption freeze sparks fresh private credit jitters,” 19 November 2025

- Financial Times, “Blue Owl calls off merger of private credit funds,” 20 November 2025

- Reuters, “Blue Owl axes private credit fund merger after market upset,” 20 November 2025

- The Wall Street Journal, “A private credit winter is coming,” 27 October 2025

- Australian Financial Review, “New credit ‘cockroaches’ just appeared. Jefferies is plunging again,” 17 October 2025

- The Wall Street Journal, “US insurers are binging on private credit, Moody’s says,” 12 November 2025

- Financial Times, “If private credit breaks, insurers will fall under the microscope,” 15 November 2025