Germany’s decision to loosen its constitutional borrowing limits marks one of the most significant fiscal shifts in Europe in recent years. Under the original debt brake, the federal government was restricted to running structural deficits of no more than 0.35% of GDP, effectively preventing large‑scale borrowing outside of emergencies1.

Berlin is now relaxing those constraints, allowing defence spending to sit entirely outside the limit and creating scope for a much larger investment push. As part of this shift, the government has authorised a €1 trillion multi‑year spending package, which includes exempting defence outlays from the cap and establishing a €500 billion infrastructure fund to be deployed over 12 years. The move comes as Germany emerges only tentatively from a prolonged slump: GDP grew just 0.2% in 2025, its first annual expansion since 2022, after more than three years of stagnation2.

The policy U‑turn reflects recognition that Germany’s economic model, built on export strength and tight fiscal discipline, has been strained by geopolitical shocks, rising tariffs, and intense manufacturing competition from China. Germany’s spending push therefore represents an attempt to restore lost momentum, at a time when the broader European economy is also fighting subdued growth.

Why did Berlin abandon its fiscal conservatism?

The catalyst for Germany’s dramatic fiscal shift is a convergence of economic stagnation and geopolitical insecurity. The economy has been hamstrung by weak manufacturing performance, with exports falling for the third straight year and shipments to the US down 7.8%, particularly in vehicles, while industrial output has declined for three consecutive years. Compounding this is Germany’s urgent need to rebuild military readiness. The country plans to spend €650 billion on defence between 2025 and 2030, more than double the previous five‑year period3.

Yet Germany’s top advisory bodies warn that fiscal expansion alone cannot compensate for deeper issues. The Bundesbank argues that only 0.35–0.5% will be added to economic growth by 2028 because €250 billion of new debt is set to cover welfare, tax cuts, and day‑to‑day expenditures rather than productive capital4. These critiques highlight that the spending push is necessary, but insufficient without structural reform.

How will Germany’s spending push impact Europe?

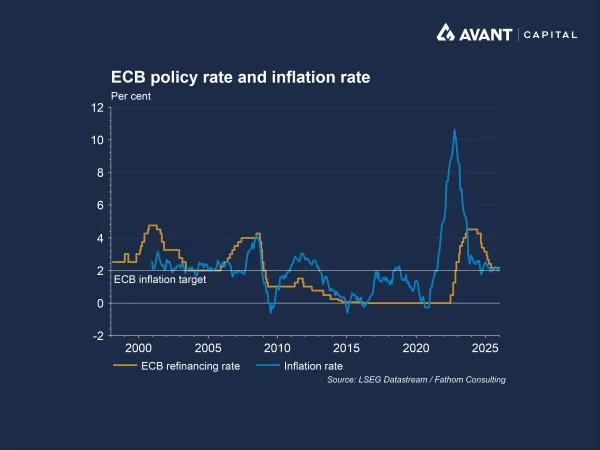

The Eurozone enters 2026 with inflation having returned to the European Central Bank (ECB)’s target of 2%5. The ECB has kept rates at 2% for four consecutive meetings, stating that policy is in a “good place.” Its own projections see Eurozone GDP growth at 1.2% in 2026 and 1.4% in 2027–2028, supported by domestic demand and earlier rate cuts feeding through6.

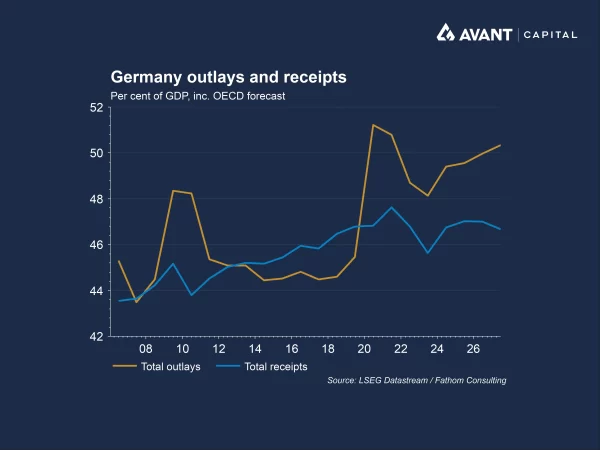

Germany’s fiscal boost reinforces this outlook. The ECB expects Eurozone governments to adopt a more expansionary fiscal stance in 2026, equivalent to increasing government budgets by around 0.3% of GDP, with Germany responsible for most of that shift7. Analysts anticipate that the peak growth impact of Berlin’s stimulus will come in 2026 as infrastructure contracts, defence procurement and tax incentives gain traction. This is reflected in forecasts: Germany’s budget deficit is set to widen from 3.1% of GDP in 2025 to 4% in 2026.

What does Germany’s spending surge mean for financial markets?

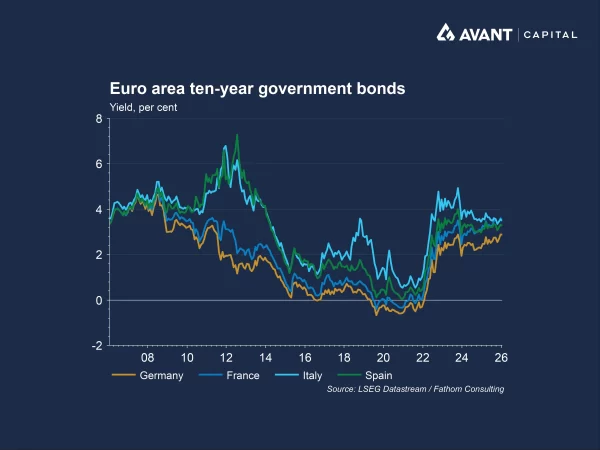

German fiscal expansion is already reshaping European capital markets. The era of ‘Bund scarcity,’ a period when German government bonds were in short supply because the ECB was buying large volumes and Germany’s debt brake kept issuance extremely low, is now over, with Berlin set to issue far more debt8.

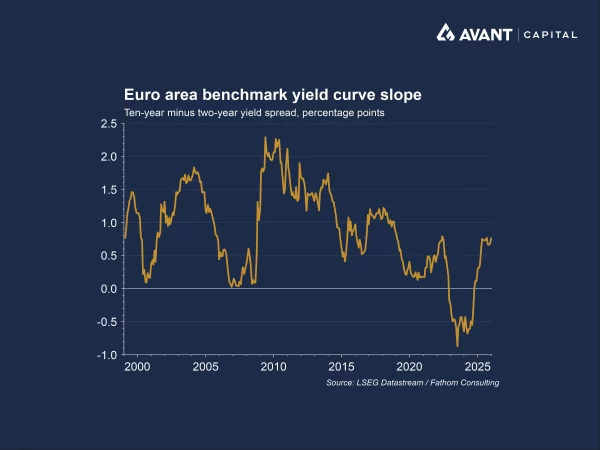

The return of more regular bond German issuance could draw investor demand away from other Eurozone issuers, putting upward pressure on peripheral yields and risking wider spreads between two-and ten-year yields as markets adjust to a rebalanced supply landscape.

Equity markets have reflected growing optimism around Europe’s outlook. The STOXX 600 advanced through 2025, outperforming major US indices for much of the year, although much of that strength came from stabilising interest rates and comparatively cheaper valuations rather than any immediate impact from fiscal measures. Defence‑related equities have continued to climb as geopolitical tensions and domestic rearmament bolster order books across the sector.

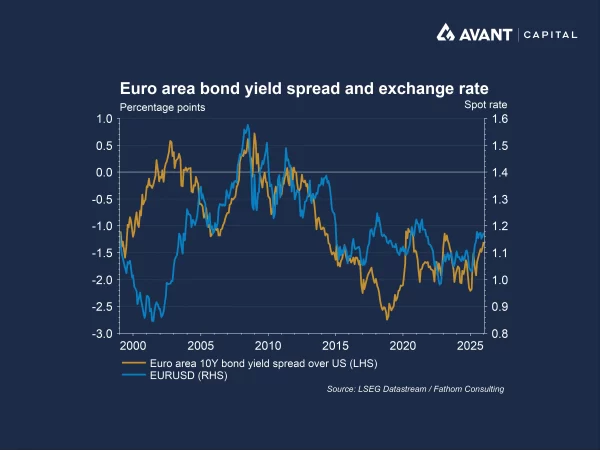

The Euro has remained relatively stable as the ECB holds rates steady, and the policy backdrop in 2026 could become more supportive for the currency. If the Federal Reserve cut rates while the ECB maintains its stance, a narrowing US–Europe rate gap could improve the relative yield appeal of Eurozone bonds and encourage capital inflows into the region.

The outlook for Europe in 2026 is therefore more constructive than in recent years. Eurozone inflation has been decisively tamed, ECB policy is stable, and Germany’s spending shift provides a meaningful uplift to regional demand.

References

- Financial Times, “Friedrick Merz’s €1 trillion spending plan wins final approval from Germany’s upper house,” 21 March 2025

- Financial Times, “German economy grows for first time since 2022,” 15 January 2026

- Financial Times, “Germany approves €50 billion in military purchases,” 17 December 2025

- Financial Times, “Germany’s multiyear recession will only fade slowly in 2026, Bundesbank warns,” 19 December 2025

- The Wall Street Journal, “Eurozone inflation falls to ECB target,” 7 January 2026

- Financial Times, “ECB holds interest rates at 2%,” 19 December 2025

- Financial Times, “Germany is reigniting cautious optimism in Europe’s economy,” 19 January 2026

- Financial Times, “Era of Bund scarcity is over, says German debt chief,” 17 June 2025