Why are Japanese bond yields rising?

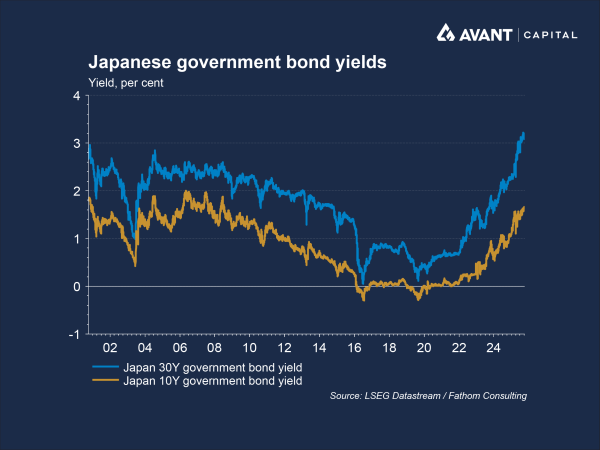

After nearly a decade of ultra-loose monetary policy and near-zero interest rates, Japanese government bond (JGB) yields have risen to their highest levels in decades. The benchmark 10-year JGB yield recently surged past 1.66%, while 30-year yields have hit 3.22%.

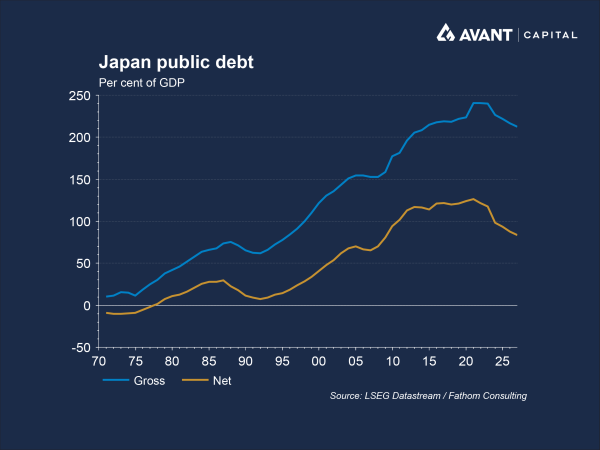

This steepening of the yield curve reflects investor concerns about Japan’s enormous debt burden, that currently sits at over 200% of GDP. Japan’s new Prime Minister, Sanae Takaichi, has also promised several new spending initiatives that may add to this debt pile, causing investors to demand greater yield compensation for holding long-dated JGBs, as they assign them a higher risk premium1.

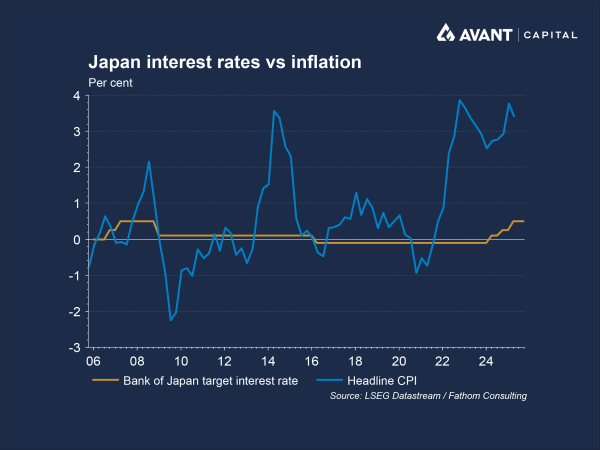

Inflation, once elusive in Japan, has now also become more entrenched, remaining above the Bank of Japan (BoJ)’s 2% target for over three years. This has forced the BoJ to gradually raise interest rates, and flag more rate hikes in the future, further pushing up bond yields2.

Why are Japanese investors pulling back from foreign bonds?

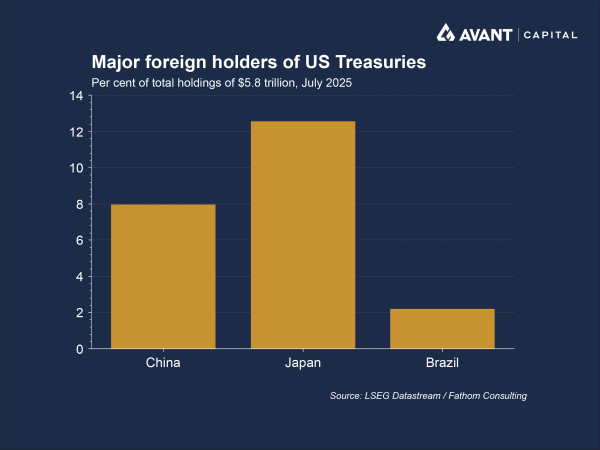

Historically, Japanese institutional investors, especially life insurers and pension funds, have been major buyers of foreign bonds, particularly US Treasuries. With domestic yields near zero, they sought higher returns abroad, often also paying to hedge currency risk and protect their returns.

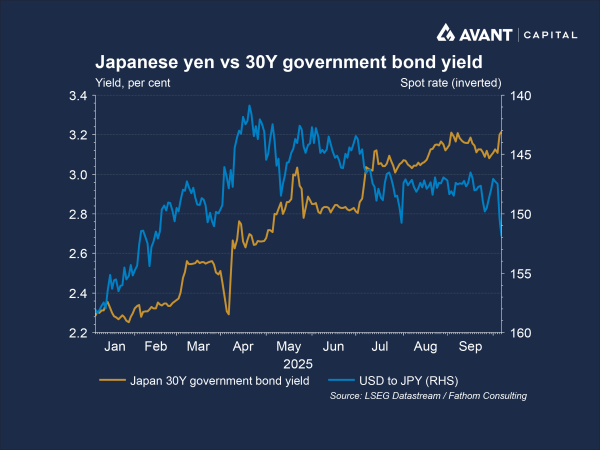

Now, however, with long-dated JGB yields rising, the incentive to invest overseas has diminished, as Japanese investors can access comparable returns domestically, without having to hedge currency risk. This shift is leading to capital repatriation as investors now buy yen-denominated bonds, strengthening the yen and reducing demand for foreign bonds2.

The unwinding of Japanese carry trades is another consequence of rising domestic yields and a strengthening yen. These trades typically involve Japanese investors borrowing in yen at low interest rates to invest in higher-yielding foreign assets. This means that as Japanese yields rise, the cost of borrowing increases, and as the yen strengthens, the value of overseas investments falls when converted back. Together, these shifts have made the carry trade less profitable, prompting investors to unwind positions and reallocate capital domestically.

Japanese investors are among the largest holders of US Treasuries and Eurozone sovereign debt. This means that as they reallocate to domestic bonds and sell international securities, global long-dated yields could rise as prices fall, forcing governments globally to issue debt at higher costs and exacerbating fiscal pressures.

How has this impacted Japanese equity markets?

The Japanese stock market is dominated by large conglomerates known as keiretsu, such as Mitsubishi, Toyota, and Hitachi, which are vertically and horizontally integrated groups with member firms that hold cross-shareholdings in one another3. An example is Mitsubishi, which includes Mitsubishi Corporation, Mitsubishi Heavy Industries, and Mitsubishi UFJ Financial Group that all maintain stakes in each other. These groups are large exporters, and benefit from a weak yen, which boosts the competitiveness of their exports, and means they can buy more yen when converting each dollar of foreign currency denominated revenue. Recent yen strength has therefore been a revenue headwind for these companies.

Despite the FX headwind for its exporting conglomerates, though, Japan’s equity market has still reached record highs4. Although demographic challenges are intensifying, with the number of births in 2024 falling below 700,000 for the first time since records began at the end of the 19th century5, Japan’s economy still grew 2.2% in Q2 20256. This marks the fifth consecutive quarter of expansion.

Japanese companies have also increasingly prioritised shareholder returns through record buybacks and dividend increases in 2025, which has further driven market gains. In April alone, Topix-listed firms announced ¥3.8 trillion ($27 billion) in buybacks – nearly triple the amount from the previous year7. This momentum has been fuelled by reforms pressuring companies, particularly those trading below book value, to improve capital efficiency, by reducing excess cash holdings and cross-shareholdings through asset sales, buybacks, and dividends.

It remains to be seen whether Japanese government bond yields will remain elevated going forward, however this will no doubt have an impact on wider financial markets and where Japanese investors allocate their capital.

References

- The Wall Street Journal, “Japan’s new Prime Minister could make rate increases tricky for Bank of Japan,” 6 October 2025

- Financial Times, “Rout in Japanese bonds heralds ‘pivotal change,’” 1 October 2025

- Investopedia, “What is Keiretsu? Definition, how it works in business, and types,” 31 August 2024

- The Wall Street Journal, “Japan stocks surge after Takaichi win,” 6 October 2025

- Financial Times, “Investors sense this time is different for Japan,” 1 October 2025

- The Wall Street Journal, “Japan’s economy continues to growth amid tariff woes, revised data confirms,” 7 September 2025

- Financial Times, “Japan’s share buybacks nearly triple as governance push gains pace,” 1 May 2025