How does the AI supply chain work?

In 2024 210 companies in the S&P 500 commented on AI opportunities in their second quarter results presentations, up from the 5-year average of 88 and 10-year average of 551. This shows more companies are looking to move into the AI supply chain by rolling it out as a direct product for their customers, and exploiting it to drive productivity gains in their operations.

The supply chain begins with hardware providers, who design and produce the equipment AI software applications run on. The best examples are semiconductor chipmakers like Nvidia (NVDA:NASDAQ), AMD (AMD:NASDAQ), ASML (ASML:NASDAQ), Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing (TSM:NYSE) and Intel (INTC:NASDAQ). These chipmakers produce the information processing chips in data centres and computers, which can handle the computation power needed to train and run large language AI models (LLMs), such as OpenAI’s ChatGPT and Google’s (GOOGL:NASDAQ) Gemini. NVDA’s chips have an edge over competitors here, as they are able to more efficiently handle the huge workloads and simultaneous calculations required in training and running AI.

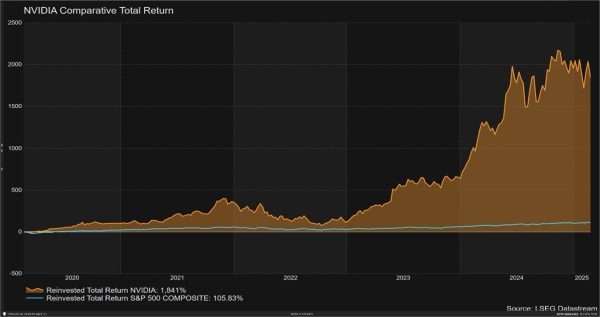

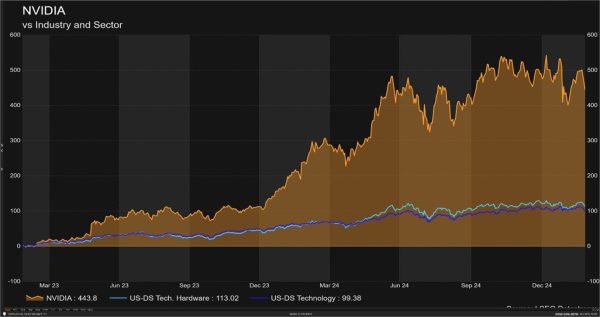

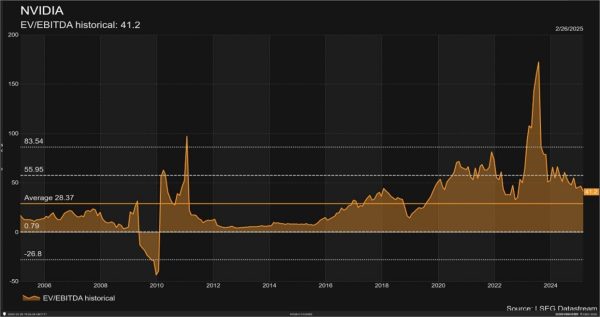

In November 2022, just prior to the release of ChatGPT and the explosion in demand for AI, NVDA earned approximately $US3 billion in gross profits each quarter, mostly from selling graphics cards to gamers. Its most recent quarterly results show gross profits of $US28.7 billion2. Its share price climbed five-fold over that time, but its earnings have grown even faster, catapulted by consistent 75-80% gross margins that highlight the pricing power its product offering commands. NVDA’s chips are exceptionally well-suited to training LLMs and are so dominant that in a bid to curb China’s AI advancements, the US banned the export of NVDA’s most sophisticated chips to China in 20223.

However, chipmakers do use different operating models. NVDA and AMD focus purely on the design of their chips, outsourcing all manufacturing to pure-play manufacturers like TSM. Whereas Intel and ASML are more vertically integrated, internally designing and building their own chips.

The next link in the AI supply chain is cloud providers like Microsoft (MSFT:NASDAQ) and Amazon (AMZN:NASDAQ), who host the data that chips use to run LLMs. These providers are intermediaries, allowing requests from users on LLMs to flow through the cloud to the chips in data centres, which can then run the computations for the LLM to generate a response. The cloud also serves as a repository that stores the data LLMs have generated in their prior responses, which they continue to learn from and use in future responses.

Together the above companies provide the infrastructure for the consumer-facing AI applications that we use and indirectly engage with. These include both new products, like ChatGPT, and augmented existing products, like Meta’s (META: NASDAQ) integration of AI ad recommendations into its targeted Facebook ads and content algorithms, which have significantly boosted engagement for their advertising clients. In the case of enhancing existing products with AI, some investors have suggested these have a leg-up over new product entrants, through their established user bases facilitating upselling and quicker adoption of new features.

The funds these AI providers spend on chips from suppliers like NVDA are classed as capital expenditure, meaning the amounts spent do not impact profit margins in the short-term, as they are not recorded as expenses but instead as assets depreciated over time. Investors argue this has been a driver of companies’ significant spending on chips to build their AI capability, as they can do this with minimal near-term impact on profitability. News in late-January that Chinese start-up DeepSeek had created a new LLM called R1, comparable in capability to ChatGPT but at a fraction of the development costs and with less chips, has caused some investors to question these bullish outlooks for chip demand however, as they argue future AI applications will be more efficient and require less chips4.

The other side of the coin for AI use is in-house applications that businesses develop or license to automate their operations and workflows, with the applications for this largely limitless and applicable to any sector where AI could drive productivity. An example is Salesforce’s (CRM:NYSE) Einstein AI, which analyses customer data to identify trends and suggest the best way to engage with customers. For sales representatives, the application provides lead scoring that allows them to prioritise leads based on the likelihood of conversion, while also automating back-office functions like customer data entry. Like consumer-facing products, these applications require both chips and cloud services.

What about Taiwan?

Taiwan produces over 90% of the world’s advanced chips5. This has raised concerns from investors about geopolitical risk, and what a potential invasion or occupation of Taiwan by China could mean for the AI supply chain. In August 2022, US Congress passed the CHIPS Act, which allocated $52 billion in subsidies to boost semiconductor manufacturing in the US and reduce dependence on foreign sources6. Newly elected President Donald Trump suggested the Act did not go far enough, placing emphasis throughout his campaign on bringing chip manufacturing to the US.

Reports in late February suggested Taiwan’s leading chip manufacturer TSM has also looked to reduce this geopolitical risk, by exploring a potential acquisition of INTC, which has significant chip manufacturing capability and factories in the US7. The potential deal would be a reversal of one explored in 2005 when INTC, then worth around $US120 billion, discussed and subsequently decided against an acquisition of the Silicon Valley start-up NVDA for $US20 billion8. NVDA is now worth $US3.3 trillion, with INTC trading at around $US108 billion.

How does electricity demand fit in?

Investors have suggested the growing use of AI will also increase electricity demand, through the chips needed for AI being in data centres, which each consume around the same amount of energy as 50,000 homes. Morgan Stanley (MS:NYSE) estimates data centres currently use around 5% of the electricity in Australia’s power grid and expects this to grow to 8% by 20309. Some have argued this will cause electricity prices for data centres and by extension chipmakers to ramp up, as there is insufficient new energy supply coming online in the near-term to meet this surge in demand.

AI demand will no doubt continue to grow and be a force in global markets, driving demand for the chip makers, cloud providers and energy producers that are critical to its supply chain.

References

- FactSet, “More than 40% of S&P 500 companies cited “AI” on earnings calls for Q2,” September 13, 2024

- Nvidia, “Financial Reports,” February 27, 2025

- Australian Financial Review, “US is planning new AI chip export controls aimed at Nvidia,” June 29, 2023

- Australian Financial Review, “DeepSeek arrival upends investor belief in magnificent seven dominance,” January 28, 2025

- Forbes, “Advanced microchip production relies on Taiwan,” January 13, 2023

- US Congress, “CHIPS and Science Act,” April 25, 2023

- Morningstar, “Intel: Best case scenario is a spinoff of design,” February 19, 2025

- Australian Financial Review, “How Intel got left behind in the AI chip boom,” October 29, 2024

- ABC, “Power-hungry data centres scrambling to find enough electricity to meet demand,” July 26, 2024