Why did the RBA cut rates?

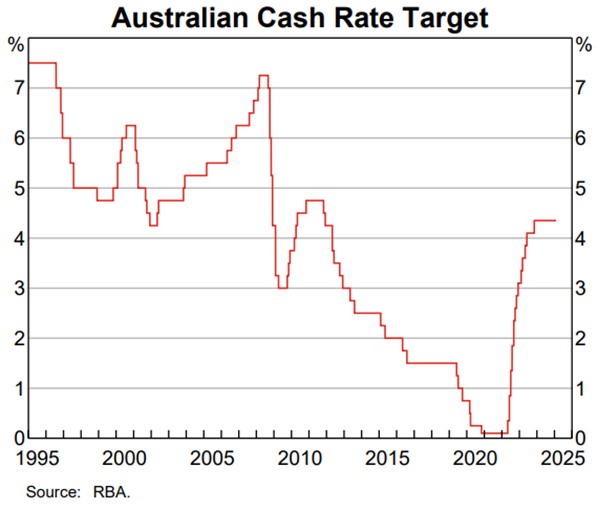

The RBA decided to cut the cash rate from 4.35% to 4.10% last week, delivering its first rate cut in more than four years. This also marked the end of an interest rate tightening cycle, which saw the cash rate jacked up 13 times between May 2022 and November 2023, from 0.10% to 4.35%1. As disrupted supply chains, global energy shocks and pandemic-era stimulus measures combined to create the worst inflation outbreak in decades.

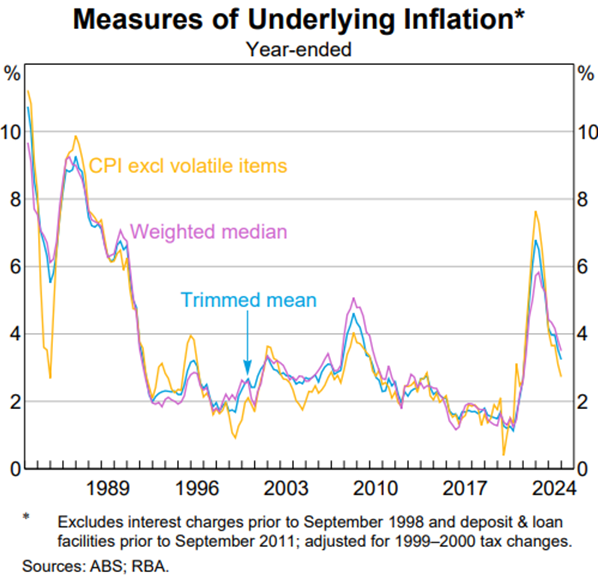

Ahead of the announcement, markets priced a 90% chance of a rate cut, spurred by the ABS’ most recent quarterly inflation report, which showed underlying inflation tumbled from 3.6% in September to 3.2% in December2, 0.2% lower than the central bank’s forecast. RBA Governor Bullock, however, undercut this perceived certainty in her press conference, stating the decision was “difficult” and far from the “lay-down misère” markets had anticipated.

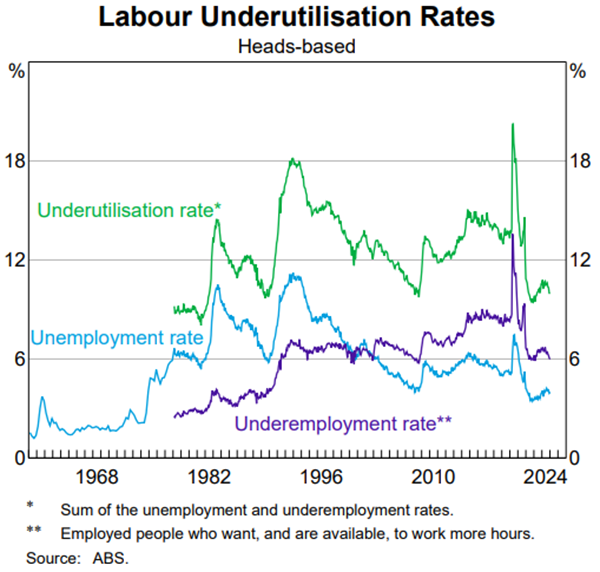

A resilient labour market and unexpected jobs growth saw the unemployment rate reach 4% in December3, close to its lowest point since the 1970s and below the RBA’s forecast 4.3%. This made the central bank wary of an increase in wages and consumer spending, which could re-ignite inflation. Bullock stated these concerns would likely keep them from cutting rates further in the near term, causing investors to trim their rate cut expectations for the year. Previously markets had anticipated two more cuts by the year’s end, which Bullock called “unrealistic.” Investors are now predicting one cut in July and no further easing until February 2026.

Lucky Chalmers?

Following their decision, the RBA board’s statement said they were “confident inflation is moving sustainably towards the midpoint of the 2-3% target range.” This is in contrast to their Statement on Monetary Policy’s inflation forecasts, which were revised up and expects underlying inflation to flatline at 2.7% by June 2025, above the 2-3% target range’s midpoint4. This disconnect caused some investors to suggest political motivations for the February rate cut, suggesting it was premature and brought forward by pressure from the Albanese Government to give borrowers some cost-of-living relief ahead of the election. As well as to highlight the government’s progress on inflation, with Treasurer Chalmers stating after the rate cut that the “worst of inflation is behind us5.”

Others argue this is unlikely, given the cooler than expected inflation figures for the December quarter, which they say justifies the decision. This is likely to also be an isolated cut, with Bullock ruling out another before the election, which will have a minimal impact on cost-of-living challenges facing voters. According to comparison website Canstar, the 0.25% cut will lower monthly mortgage repayments by $77 for a household with a $500,000 mortgage, by $115 for a $750,000 mortgage, and by $154 for a $1 million mortgage6.

How do changes in interest rates impact markets?

Interest rates and the stock market tend to move in opposite directions. As rates fall, debt servicing costs decrease, which increases profits for companies depending on their level of indebtedness. Consumers receive similar gains, with borrowing costs for mortgages and other debts similarly falling, spurring discretionary spending as they put less funds towards servicing debt. This can cause consumer demand and companies’ sales to rise, particularly for those in more discretionary sectors, where customers are inclined to increase spending more than in staple sectors like supermarkets, where spending is more fixed.

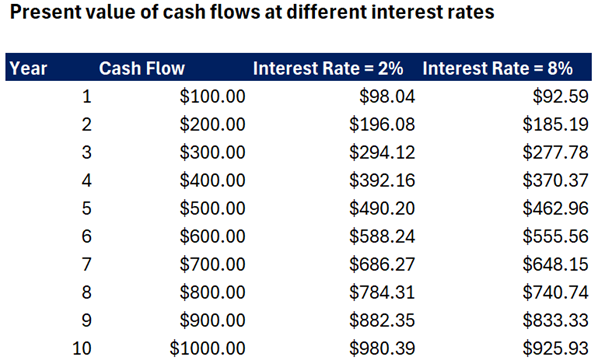

Interest rate changes also impact company valuations. The most common valuation method is the discounted cash flow model (DCF), which is based on the idea that a stock’s worth is equal to the present value of all its estimated future cash flows. These future cash flows are inherently uncertain, which means to calculate their present value, we need to discount them by an appropriate discount rate. Which represents the minimum return we require for taking on this uncertainty and investment risk. This minimum return is measured as the return we could earn if we invested our money elsewhere, and usually involves using the interest rate on risk-free government bonds as a starting point, as this represents a comparable return we could be earning.

The RBA’s cash rate is one of the key drivers of the risk-free rate on government bonds, meaning it has a significant impact on the discount rate investors use to value companies. As the cash rate goes down, this then causes future cash flows to be discounted at a lower rate, increasing their present value and companies’ overall valuations. This can be a particular benefit for growing companies’ where most profits are still years away, as these profits will now be discounted at a lower rate, raising valuations.

Movements in the interest rates offered on government bonds due to the cash rate also impact the relative attractiveness of stocks as an investment. Given investors take on more risk investing in stocks relative to risk-free government bonds, they expect a higher return from stocks as compensation for taking on this additional risk. If the cash rate and rates on government bonds fall, while the expected return on stocks remains the same, this typically causes investors to buy stocks and sell bonds, as they believe the added risk from investing in stocks is justified by their now greater extra return.

While these factors combine to make markets more often than not go up when interest rates are falling, this has not been the case following the RBA’s February rate cut, with the ASX 200 down following the decision. This may be due to investors already expecting the cut before the announcement, meaning its anticipated benefits for consumers and companies’ prospects were already being priced in, and investors instead focused on the central bank’s hawkish guidance for future rate moves.

Whatever your view on the RBA’s decision and investors’ reaction to it, we will continue to keenly monitor central bank interest rate moves and their impact on markets and the global economy, with great interest.

References

- Reserve Bank of Australia, “Statement by the Reserve Bank Board: Monetary Policy Decision,” February 18, 2025

- Australian Bureau of Statistics, “CPI rises 0.2% in the December 2024 quarter,” January 29, 2025

- Australian Bureau of Statistics, “Unemployment rate rises to 4.0% in December,” January 16, 2025

- Reserve Bank of Australia, “Statement on Monetary Policy – February 2025,” February 18, 2025

- 9News, “’Worst of inflation is behind us’: Jim Chalmers addresses interest rate cuts,” February 19, 2025

- Canstar, “The RBA has cut rates for the first time since 2020 – what could it mean for your home loan?” February 18, 2025