What is happening in Japanese bond markets?

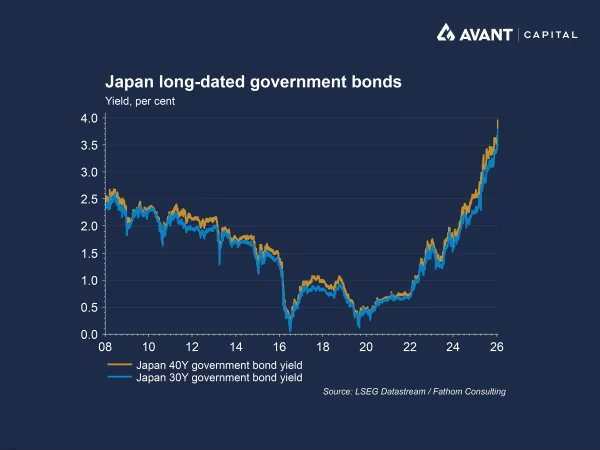

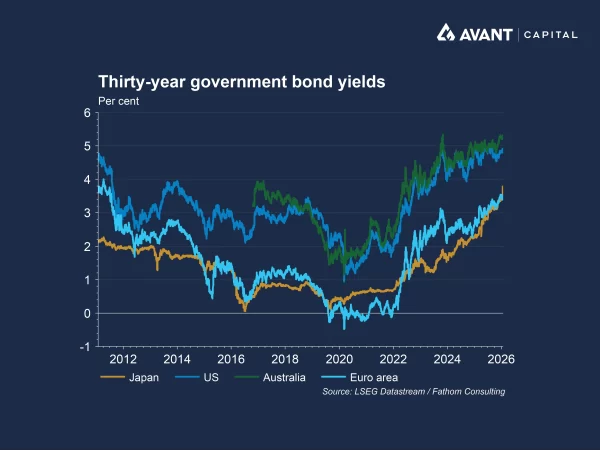

Long‑term Japanese government bond (JGB) yields have surged to levels unseen in decades. Japan’s 40‑year yield recently crossed 4% for the first time since that maturity was introduced in 2007, with one episode pushing yields to about 4.2% amid heavy selling1. This rise has been driven in part by expectations that Prime Minister Sanae Takaichi’s proposed fiscal expansion, including a planned two‑year suspension of the 8% consumption tax on food, will increase government borrowing and worsen an already elevated debt load. Japan’s public debt, which has been as high as 250% of GDP in recent years, and the prospect of further stimulus has made investors demand higher compensation for holding ultra‑long‑dated bonds.

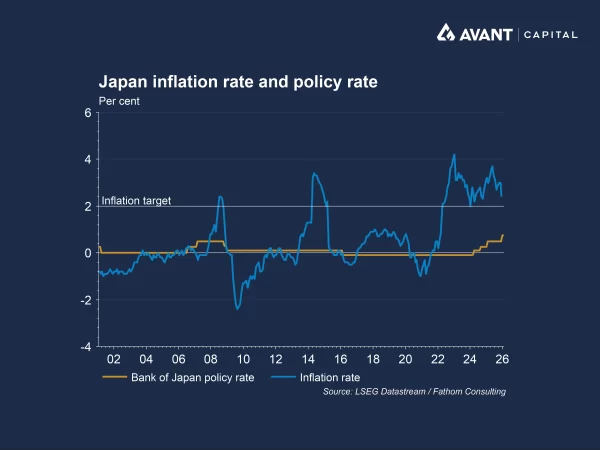

At the same time, the Bank of Japan (BoJ) has shifted away from its ultra‑loose monetary policy. The policy rate now stands at 0.75%, the highest in three decades2. Even though this rate remains low by global standards, the move signals ongoing normalisation, and markets are increasingly pricing additional hikes. Rising inflationary pressures, firmer wage dynamics and uncertainty around government spending have collectively pushed JGB yields higher across maturities.

Why has the yen rebounded and what does FX intervention mean?

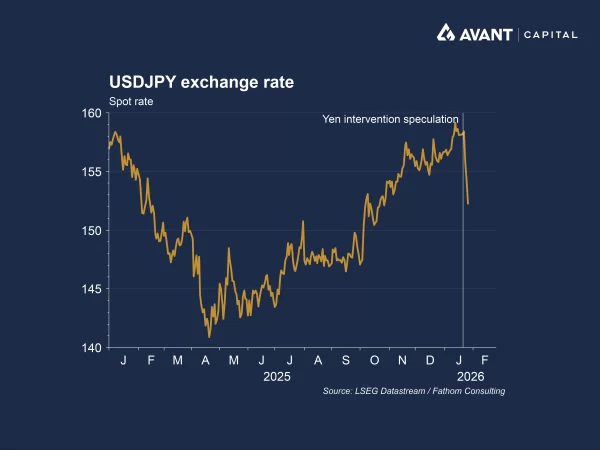

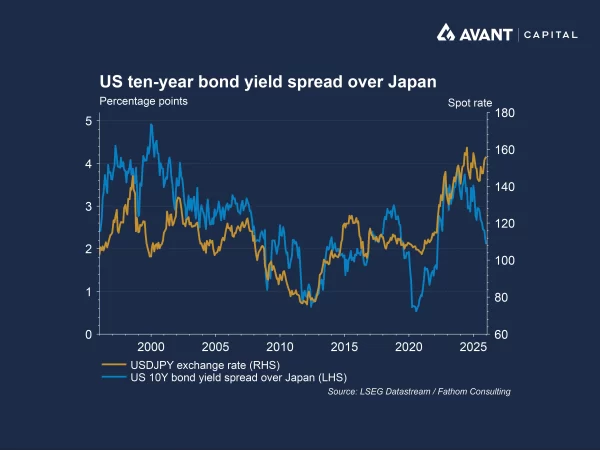

The yen has strengthened sharply in recent sessions after falling near ¥160 per US dollar earlier this month, levels that historically prompted intervention3. Much of the move was triggered by a so‑called “rate check” conducted by the New York Federal Reserve at the request of the US Treasury, where officials contacted banks to ask where they would transact yen if authorities stepped into the market. Although a rate check is not the same as direct intervention, it is widely understood as a warning shot, a signal to traders that authorities may be preparing to buy yen using dollar reserves to halt excessive depreciation. This has fuelled speculation that Japan and potentially the US could be preparing coordinated action to buy yen and stabilise the exchange rate, prompting traders to reposition swiftly in anticipation of a move.

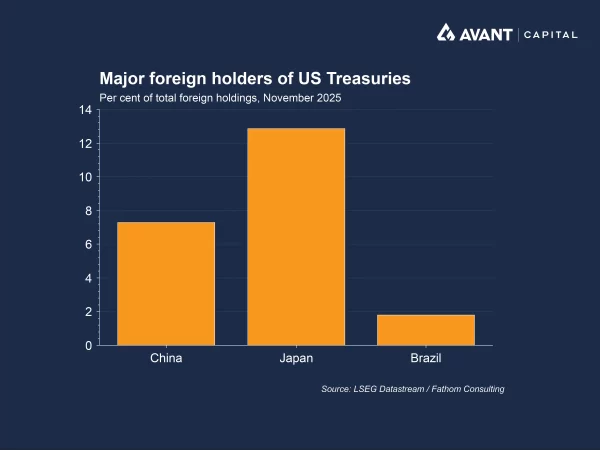

FX intervention occurs when governments or central banks buy or sell currencies in the market to influence exchange rates. Japan typically buys yen (and sells dollars) when it wants to strengthen the currency. The US Treasury can also participate via its Exchange Stabilization Fund. Recent yen‑intervention speculation reflects concerns shared in both Tokyo and Washington. Japan is focused on the inflationary impact of a weak yen, which raises import costs and intensifies pressure on households. For the US, the issue is not the currency level itself but what the yen’s weakness signals; disorderly moves in Japan’s bond market. Sharp rises in JGB yields have already spilled over into global bonds markets, and Washington fears that further instability could prompt Japanese investors, who hold roughly 13% of the US Treasury market, to repatriate capital, which could put downward pressure on Treasury prices and push US yields higher4. Stabilising the yen is therefore seen in Washington as a way to restore confidence in Japan’s bond market, reduce volatility in global rates, and protect the stability of the US Treasury market.

How are Japanese equities responding?

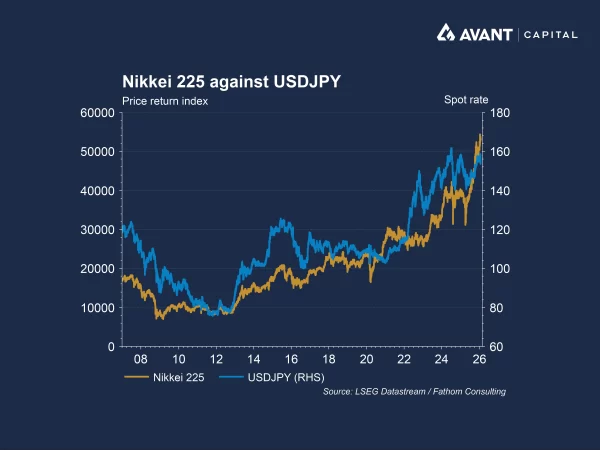

Japanese equity markets have reacted negatively to the yen’s rebound. A stronger yen reduces the value of overseas earnings once converted back into yen, a concern for Japan’s globally diversified exporters such as Mitsubishi, Honda, Nissan and Panasonic.

Investors had been positioned for what some called the “Takaichi trade,” expecting strong equity markets driven by Prime Minister Sanae Takaichi’s fiscal expansion. But rising yields have now reached levels that could be counterproductive for economic growth and financial stability. As the yen appreciates on intervention speculation, this trade has begun to unwind, placing pressure on Japan’s stock market.

What are the implications for global bond markets?

Global spillovers are emerging because of the deep financial linkages between Japan and the rest of the world. With JGB yields rising faster than those of many foreign sovereign bonds, especially when hedging costs are considered, the incentive for Japanese investors to shift capital back home has increased. Japanese investors are the largest foreign holders of US Treasuries, owning around $US1.2 trillion, meaning any meaningful repatriation could put downward pressure on Treasury prices and upward pressure on yields5.

However, analysts remain divided. Some argue that a mass shift out of Treasuries is unlikely, given liquidity constraints in the JGB market. The US Treasury market is more than four times the size of the JGB market and trades more than $US1 trillion a day, far exceeding Japan’s thin long‑dated issuance. For Japanese investors managing large pools of capital, such as insurers and pensions, replicating US‑scale transactions domestically is impractical.

Yet even if large‑scale flows may be unlikely, marginal shifts still matter. Rising JGB yields set a higher floor for global interest rates, influencing how investors price risk everywhere from the US to Europe. Higher Japanese yields can also ignite volatility in global bond markets, particularly when foreign investors use JGBs as reference points for relative‑value trades.

How might the yen carry trade be affected?

If the yen strengthens rapidly, traders can face sudden losses because the currency they borrowed in becomes more expensive to repay, forcing them to unwind positions at unfavourable levels. What was previously a profitable trade, borrowing cheaply in yen to invest in higher‑yielding foreign assets, can quickly flip into a loss as the rising yen erodes returns and squeezes leveraged investors who must buy yen back at a higher price to close out their funding positions. This combination of rising JGB yields, a strengthening yen and heightened intervention speculation therefore makes the outlook for bond and currency markets highly uncertain.

References

- Financial Times, “Japan’s Sanae Takaichi vs the bond markets investors place their bets,” 21 January 2026

- The Wall Street Journal, “Bank of Japan keeps rates at 30-year high as it gauges impact of last hike,” 23 January 2026

- The Wall Street Journal, “Wall Street is fixated on a possible yen intervention,” 26 January 2026

- Financial Times, “The Japanese yield panic,” 23 January 2026

- Financial Times, “Maybe we’re all doomed. Or maybe Japanese bonds are getting cheap,” 21 January 2026