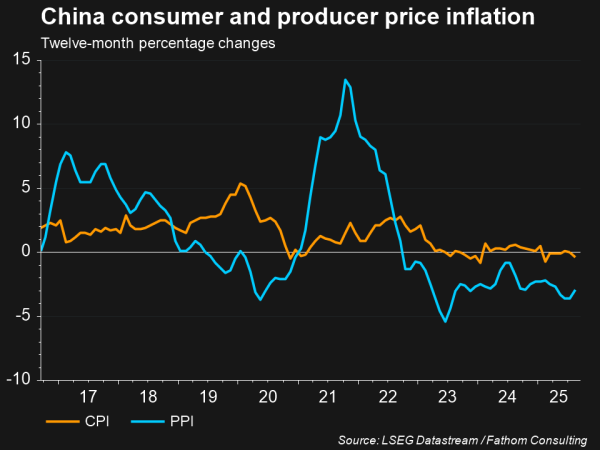

China’s headline consumer price index (CPI) fell 0.4% year-on-year in August, slipping back into deflationary territory after a flat reading in July. Producer prices also dropped 2.9%, marking the 35th consecutive month of producer deflation1. These readings highlight how China’s deflation is not merely cyclical, but reflects structural supply-demand imbalances in the Chinese economy.

What has caused these imbalances?

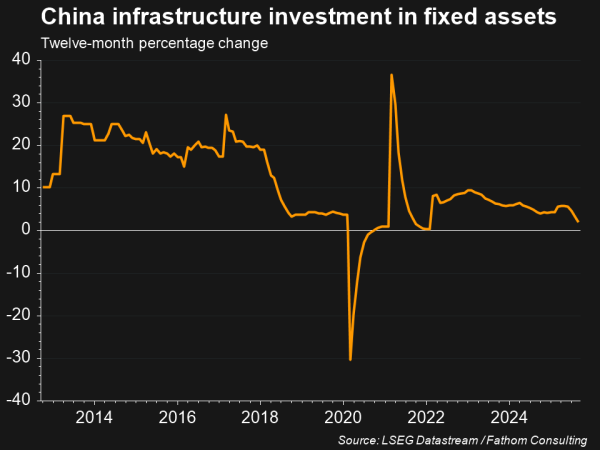

The roots of China’s deflation lie in the country’s long-standing reliance on investment-led growth, particularly in manufacturing and infrastructure2. For years, China’s economic model prioritized rapid expansion through large-scale construction and the relentless building of new capacity. This approach was especially pronounced after the bursting of the property bubble in 2021, when policymakers doubled down on investment to offset the drag from a weakening real estate sector. As property-related activity cooled, the government sought to compensate by ramping up investment elsewhere, further fuelling the expansion of manufacturing capacity even as underlying demand began to falter.

This surge in supply has then led to duplicated capacity, and excessive competition (or involution), prompting price wars as more goods flood the market, and companies are forced to cut prices to maintain market share3. These lower prices have then, however, been unsuccessful in stimulating demand domestically or abroad (via exports), resulting in the economy’s structural oversupply.

Why has Chinese consumer demand remained subdued?

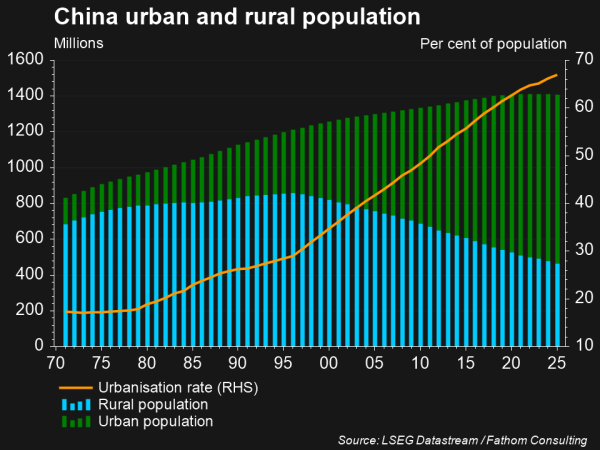

Weak Chinese consumer demand has been caused by the property market’s ongoing woes, as Chinese households have constrained their spending due to their household wealth, which is heavily tied up in real estate, continuing to fall. Precautionary savings have therefore remained high, as consumers view their financial position as deteriorating.

China’s falling population has then compounded this spending issue, even as urbanisation rates have continued to rise.

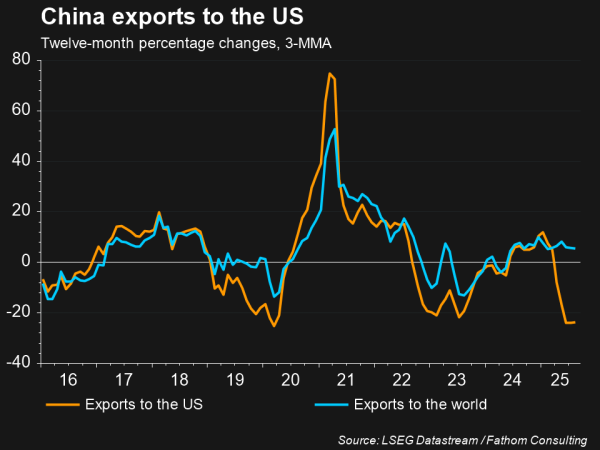

How have tariffs impacted demand for Chinese exports?

In August 2025, export growth fell to 4.4% year-on-year, the weakest pace in six months and below market expectations. Imports rose just 1.3%, also trailing July’s figures. Particularly striking was an over 20% plunge in exports to the US, a direct consequence of President Trump’s elevated tariffs4. While China has managed to increase shipments to Southeast Asia and the European Union, the loss of US market share has weighed on the country’s export-driven growth model. This has then driven deflation, as products that would be sold to the US are now being directed to domestic markets.

How has the government responded?

The government’s primary efforts to stimulate consumption has been through subsidies for consumer loans, where they will subsidise, and effectively cut, interest rates on loans for purchases up to around $US7,000. The CCP hopes this will support bank profits, rather than if they directly cut interest rates, while increasing consumer confidence. To date, however, the program has had a negligible effect on inflation. On the supply side, the government has launched an “anti-involution” campaign that aims to curb excess capacity and cut-throat competition, with authorities pressuring industries such as steel, cement, EVs, to reduce output.

Whether these policies will be successful in stimulating demand and addressing the Chinese economy’s overcapacity remains unclear, however, particularly against the backdrop of a declining population and potential ongoing US tariffs.

References

- The Wall Street Journal, “China’s deflationary woes continues,” 9 September 2025

- Financial Times, “What can really cure deflation in China,” 18 August 2025

- Financial Times, “China’s battle with deflation isn’t just a demand problem,” 27 July 2025

- The Wall Street Journal, “China’s export momentum slows, missing expectations,” 7 September 2025