Software stocks across global markets have suffered a sharp sell‑off in recent weeks, prompting investors to question whether a sector long regarded as one of the most resilient pillars of the modern economy is undergoing a deeper structural reset. The driver was not weaker earnings, deteriorating fundamentals or a broad macroeconomic shock. Instead, it was a sudden surge in concern that rapidly evolving artificial intelligence technologies could erode the traditional competitive advantages of software companies, challenging long‑held assumptions about the durability of their business models.

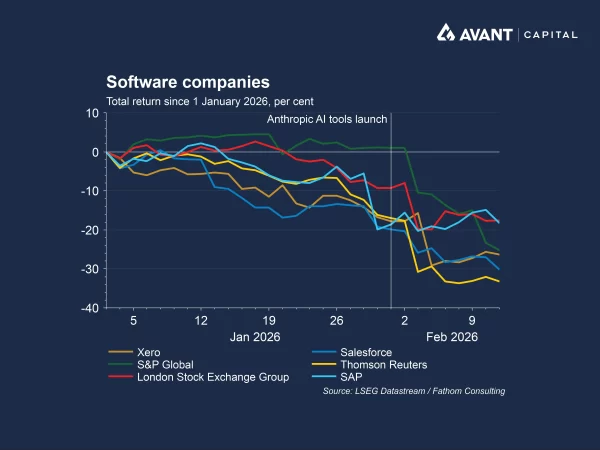

At the centre of this shift is Anthropic’s rapid development of artificial intelligence (AI) tools that can automate a growing number of professional tasks, including coding, legal review and workflow automation, with minimal human input. The launch of new plug‑ins for Anthropic’s Claude Cowork platform, particularly those aimed at legal and financial services, intensified market fears that the core functions of many long‑established software providers could be replicated cheaply and quickly by AI. These concerns triggered substantial declines across companies that specialise in analytics, data services, legal software and financial software, as investors rushed to reassess whether their business models remain defensible in an AI‑enabled economy.

Why is AI generating such strong fears now?

AI is not new to the software conversation, but recent developments have sharply intensified the perceived threat. For years, companies such as Salesforce and Xero have been valued for their high levels of recurring revenue, strong customer retention and mission‑critical roles within business operations. However, Anthropic’s new tools, which allow users to build applications through “vibe coding,” a natural‑language approach to software creation where users describe what they want and the AI assembles the code, have raised legitimate questions about where value in the software stack will sit in the future.

Market reactions have been swift. Analytics groups such as S&P Global and LSEG have fallen double digits, while legal technology providers including Thomson Reuters have also slumped. The assumption driving these moves is that if AI tools can automate the tasks that specialised software exists to handle, then the economic moat around these products could shrink dramatically.

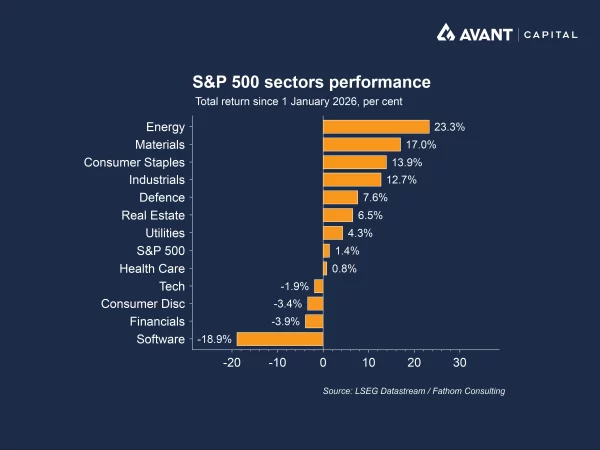

How broad has the sell-off become?

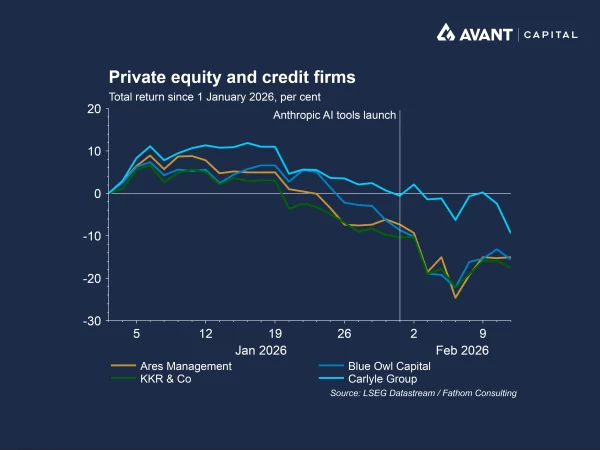

Although the focus has been on software businesses, the sell‑off has spread far wider. Private equity and private credit firms, many of which hold substantial exposure to software companies, also saw their shares fall sharply. Groups such as Ares, Blue Owl and KKR experienced double digit declines, reflecting concerns that the valuations of private software assets may need to be marked down significantly if public market pricing persists.

Meanwhile, debt markets have also shown signs of strain. Loans issued by software companies such as Cloudera and Qlik fell meaningfully in price, and some banks struggled to syndicate new loans backing software acquisitions. Because a large share of leveraged‑loan and private credit portfolios is tied to software, any structural concerns about the sector’s ability to maintain growth pose risks to lenders as well.

The reaction was even felt in adjacent tech sectors. For instance, chipmakers fell on concerns that if software companies reduce spending, hyperscalers such as Amazon and Microsoft may experience softer demand for cloud computing resources. This illustrates the interconnected nature of the technology ecosystem and why fears about software can ripple across the market.

Are these concerns ultimately justified?

The market angst rests on an important question: will AI replace software, or will it enhance it?

Industry leaders argue the latter is more likely. Nvidia’s CEO recently referred to the idea that software will be replaced by AI as “the most illogical thing in the world,” noting that enterprise software involves far more than code, including compliance, data management and specialised workflow design1. Similarly, executives at firms like Blue Owl and Blackstone have emphasised that AI is more likely to become a distribution channel for software companies rather than a full replacement.

There is strong logic to this view. Complex platforms used for accounting, payroll, CRM or logistics require deep domain expertise and ongoing updates as regulations and industry standards evolve. Xero, for instance, highlighted that while AI can assist with tasks, it cannot yet manage the compliance, localisation and workflow complexities that underpin its products. Salesforce and Adobe similarly maintain that data, integration and support create significant barriers to replacement.

Still, valuation pressure is likely to persist. With software companies already trading on elevated multiples, even a modest slowdown in growth could trigger a meaningful de‑rating. The concern is not that AI will render established platforms obsolete overnight, but that it may compress top‑line expansion as customers revisit the size of their software budgets and increasingly use AI to build simple in‑house applications, reducing their reliance on external vendors.

In this environment, the challenge for software companies is not simply to sustain growth, but to demonstrate convincingly that they can integrate AI so that it enhances, rather than erodes, their competitive advantages.

References

- The Wall Street Journal, “AI won’t kill the software business, just its growth story,” 4 February 2026